He exuded confidence and impatience. Traveling the world and teaching with passion takes a lot of energy. Even if Alvaro Castagnet dove into the class with the verve familiar to those who devour his passionate-painter videos, we could tell he was a touch more stretched than the paper in front of him. But he smiled, and laughed, and taught us with his trademark generosity.

De’s Artroom brought Alvaro Castagnet to Manila, and opened slots for the three-day masterclass early this year. I missed the first day, but that made me more determined to absorb as much as I could over the two remaining days. The class fee included a Daniel Smith Alvaro Castagnet set. (Luckily for my underprepared ass.)

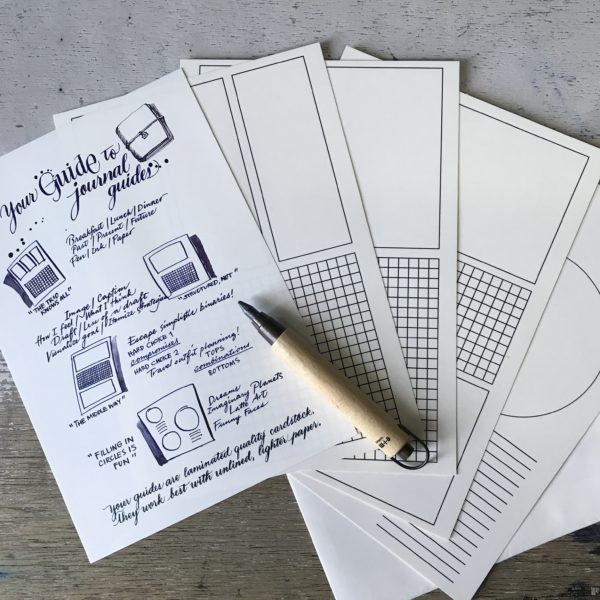

That I had not picked up a watercolor brush larger than a no. 4 in the last six months showed. Fountain pen ink moves nothing like watercolor. Their liquid nature belies the essential difference: fountain pen ink is commonly a dye, watercolor is pigment and binder. Fountain pen-friendly paper needs to be smooth and feather-proof; watercolor shows up better on 100% cotton paper with obvious texture.

Alvaro demonstrated how to create a painting that told a story from a reference. He revealed techniques for well-blended washes (“Tilt the paper!†“Keep that brush moving!â€) He stressed the importance of keeping the underdrawing loose.

I’m a doodler. This was my sad attempt at the exercise.

I’m a doodler. This was my sad attempt at the exercise.

“Big brush, small paper. That’s how you build confidence.â€

The funny thing is, I knew exactly the feeling he was patiently explaining to us. It was what I felt when I had no stakes, spattering ink on paper, pushing the edges of blots outward with my fingers, deciphering the shapes as the ink spread without me telling it where to go. It was the openness of playing, the freedom granted by skill and experience. I didn’t have it in watercolor. I could recognize it when I held a pen. Unlike Alvaro, however, I never committed to the work. It was what I had always resisted: a goal.

Watching a master at work changes your vocabulary. You know that scene in The Matrix, when Neo leaps into the body of Agent Smith, and reprograms then erases him in cinematically dramatic desaturated fashion? Something like that. Without the explosions.

“Use less brushstrokes. More brushstrokes, more uncertain.â€

Below, a picture of the Navotas port that a friend took, and Alvaro’s painting. In this exercise, he showed us how to make daring color choices (the green on the water, the Verditer Blue on the foreground boat – “it could be too opaque, but we’ll seeâ€). I asked how to get my darks to look dark. “Burnt sienna, ultramarine, no water.â€

I attempted the boat. I overblended the sky into an indeterminate lavender, so I adjusted the entire palette to fit. It was obvious to me I could not use green.

I look at that painting and I don’t recognize me. What an odd sensation, for the work of my hands to be a stranger; but it is. Alvaro said, “Very good,†and “lose that triangle on the right.†I will treasure that “very good†forever. But “lose that triangle on the right,†even more. I didn’t even know I had unconsciously mimicked the key shape on the left.

None of my doodles has a sense of place. I avoid drawing horizons. Perspective is commitment.

“I don’t care about your process. What I see is the result.â€

My classmate Sarah captured this quote:

“What makes you be a good artist is having a heart that frees up your visions. You got to have visions that are uniquely yours. You need to have the ability to express it.â€

I can sense changes after the class. I’m drawing less lines. (Gasp.) I’m planning to buy progressive glasses. (Sigh.) I don’t want to be a mini-Alvaro, and he wouldn’t want that either.

Maybe one day I’ll understand heart and vision. Until then, I’ll practice my washes.