A pointy or chisel end, a pigmented liquid, a surface, some capillary action, and a little surface tension. You could be writing with a sharpened stick or a highly-engineered fountain pen, and those ingredients would come into play, either way.

We are first attracted to how a pen looks, and the attraction is validated or negated by how the pen writes. (This is very much like salivating over a symmetrical face and a six-pack until the owner of said attributes attempts a conversation.) If the pen is the body, the nib is the mind.

Not all ends need to be pointy. Several pens meant for calligraphy have plates, essentially two surfaces almost touching each other, with space in between to suspend ink. The writing edge is notched to allow ink to flow to the paper at a measured pace.

When there are plates, there’s no need for a feed. The nib itself is also the feed. A single dip is enough for a few large letters, in the case of this horizon pen. Â Without a feed, the nib is much easier to clean, and no risk of clogging means other water-soluble media like shellac-based inks can be used, with care and much rinsing.

A modern pen with an ink supply and plate nibs is, of course, the Pilot Parallel. Available in a variety of widths, Pilot Parallel pens are a part of every calligrapher’s arsenal.

Pilot Parallel pens can deal with watercolor and gouache, as well as fountain pen ink. Use with care, have fun, rinse.

A curious variation on the plate/folded nib is the Mitchell witch pen, whose design permits a hybrid plate + reservoir. The pen can hold more ink than it looks like it can at first glance.

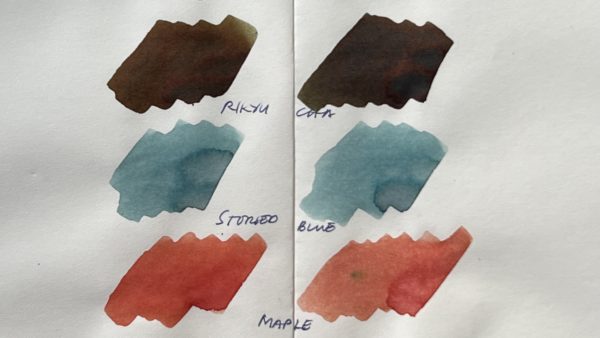

Even with all the ink it can hang on to with just one dip, the witch pen rinses clean with just a few quick swirls in water. That makes it a great ink testing pen – in fact, that’s what I use it for.

Dip pens nibs are widely available today, over a century past their heyday. Japanese manufacturer Tachikawa ships its calligraphy nibs with reservoirs.

A reservoir behaves like a feed. Ink flow can be inconsistent, though. Freshly dipped, the nib releases gouts of ink, then sometimes stutters.

Early fountain pens attempted to solve the inconsistency with feeds. Here’s an early Paul Wirt taper cap with only an ebonite overfeed.

Look ma, nothing underneath.

Even with only an overfeed, the nib kept up with a few thick-thin practice strokes.

Later on, feeds came into the picture, looking quite close to modern feeds. They used to be carved out of ebonite; modern feeds are usually plastic. Feeds have a channel and fins to help encourage and regulate capillary action. The interaction between nib and feed is crucial to the performance of the pen.

Marrying modern utility with the flair of vintage nibs is no easy task; still, Pilot’s Custom 845 in vermillion urushi comes close. The no. 15 FA nib is adequately supplied with ink by the feed (unlike its no. 10 sibling – nibling?) and shines in everyday use.

This is a pen where body and nib are in perfect accord, and it did not take long for it to graduate from the “keep-in-cabinet” pen case to the everyday carry in my backpack.

“Mens sana in corpore sano.” A sound mind in a sound body, as appropriate for the well-lived as it is for the well-written life.

(Editing this entry to supply links of interest.)

More folded nib fun can be had with Matthew Morse (@heymatthew on Twitter and Instagram).

Get your horizon brass pens from Paper Ink Arts.

The Pilot Custom 845 in vermillion urushi is exclusive to Tokyo Quill.